An anatomy of denim

An entire industry is built on one iconic fabric, a twill weave made from a warp-dyed indigo and a weft, left white. This specific weave pattern produces one of the defining features of the storied fabric, its predominately blue face and mostly white back. As fashion trends evolve towards more authentic looks, richer textures and bolder slubs are back, reviving what makes a denim fabric so special, its character.

For decades, the utilitarian past of a fabric originally made to sustain arduous working conditions was swept away by fashion trends. An infinite variety of washes, distressing and finishing techniques were, and continue to be, developed to feed the need for novelty.

With the introduction of elastic yarns, jeans embraced the notions of comfort and fit, further fuelling its steadfast success as one of the world’s favourite items of clothing. Skinny styles, for women and men alike, have long dominated the market. “Elastane has been the engine that powered nothing short of a revolution in denim, which was traditionally very rugged and outdoorsy. Elastane helped birth one of denim’s most popular items ever, women’s stretch denim,” says Baber Sultan, director of product development and R&D for Pakistan-based Artistic Milliners.

While stretch denims undeniably drove denim sales for years, signs of a shift to looser and more rugged styles are nonetheless under way. Designers are now pushing for a return to authenticity and to more durable, and possibly more sustainable, denim fabrics and styles.

The workwear trend is making a strong comeback, says Adriano Goldschmied. “The functionality of uniforms made for the women who worked in factories in the UK and the US during WWII, when the men were fighting on the front, are very inspiring for today,” he tells Inside Denim. While he is critical of mills that “always want to produce more at cheaper prices”, he has hopes that “the new generation, which is more sensible, will push for more durability and more sustainability” – causes that he actively supports in his own work.

The workwear trend is driving the revival of authentic weaves and a true denim renaissance, says denim designer Mohsin Sajid, founder of design and consultancy agency Endrime. This, he says, comes after years of “cutting corners, overlocking edges and baggy lightweight fabrics.”

“There is a move to highlight the original craft and identity of denim, and to shift away from mass market products,” says Tilmann Wröbel, denim designer and founder of design and consultancy agency Monsieur T. “It is leading to the development of denim fabrics that have a richer hand feel, more slubs, and bigger slubs, like those of authentic vintage denim fabrics. In the current context, there is a desire for higher quality jeans that last longer,” he points out.

Enduring legacy of twill

The iconic twill construction that defines a denim fabric is rooted in the utilitarian origins of jeans and overalls. Each of the founding brands chose to develop a specific weave pattern as a key differentiation point. “When jeans were first developed 200 years ago, durability was the most important feature and a twill weave delivers that strength and resistance,” says Baris Ozden, product manager for Turkey-based Isko. “Levi’s were originally made in a right hand 3x1 twill, Lee chose to develop a left hand 3x1 twill, and Wrangler introduced the broken twill as its signature weave. A broken twill prevents the skewing of the fabric on the legs,” he says. Twills in 2x1 patterns are said to be even stronger, but now developed in lighter weights, for tops mainly.

It is a limited series of weave patterns that define the world of denim. Mills have, of course, since expanded into many other patterns, including satin, 4x1 or even 6x2 constructions. “Whatever the case, and even in the knit-look fabrics we develop, our aim is to reproduce the distinctive diagonal twill lines,” says Mr Ozden. It should be noted that these weave patterns create a warp-dominated fabric and present a dominant indigo outer face. “A 3x1 twill is roughly 70% warp, and blue, while the back will be roughly 75% white. These are the roots of denim,” he says. He adds that 3x1 right hand twills continue to dominate the market and may even represent 90% of all denims made.

For Mohsin Sajid, twill is truly a “clever construction” as it gives “the illusion that the entire fabric is indigo. This cost-saving measure is now one of the distinguishing features of denim”. There is another reason for the limited range of weave patterns, he notes, as in the early days, it allowed mills to keep the same warp, and offer variety by changing the course of the weft yarn.

The beauty of imperfection

A yarn’s make plays a key role in the look and feel of a denim fabric, as denim experts are quick to point out. Before the arrival of smooth, uniform yarns made by modern open-end spinning machines, denim was woven with ring-spun yarns, their irregular surface creating coarser textured fabrics.

“Authentic denim is made with ring spun yarns, which create variations and imperfections. This is what we want,” says Mark Ix, Advance Denim’s marketing director for North America. “Ring spun yarns make it possible to play with different textures, there is a lot of opportunity for creativity,” he says, adding that these yarns can be made to have rounder or sharper slubs. He pushes further the quest for the original look and feel of denim by promoting Supima cotton. “The best denim fabrics are those that are made with long staple Supima cotton. It creates a different shine, feel, softness, it really delivers. A good fabric starts with a good yarn,” he says.

As mills sought to produce more and faster, open-end yarns became the norm. They reduced glitches and problems with machinery, leading to more efficient and consistent production runs. “Everyone loved it and denim became even more popular,” says Mr Sajid, but this is when jeans became fashion items. “Open-end yarns are not as strong as ring spun,” he says.

Historically, “yarn spinning was not as regular, there were imperfections, and those irregularities became an important feature of denim,” agrees Mr Ozden, at Isko. “Today’s spinning machines are faster and form ‘perfect’ yarns. To reproduce the original ‘imperfections’ of vintage denim, we engineer the slubs into the yarns.”

Purists will grumble that this is faux vintage. “A fabric made on an original shuttle loom with ring spun yarns will have a completely different hand feel. The weft yarns are less taught and create more texture,” says Mr Wröbel. For others, the quest for efficiency is part and parcel of industrial evolution. “Today, ring spun effects are designed into the yarn by computer, this makes it possible to engineer the unevenness and spacing of slubs,” notes Mr Goldschmeid.

The vintage look

China-based Panther Denim uses both ring-spun and open-end yarns, but Polly Cheung, its senior project manager, says demand for open-end is decreasing due to a shift in trends. “We are emphasising slub and character and tuning our weaving machines to address the emerging trend for more texture,” she tells Inside Denim. The 3x1 twill remains its core business. “It is the roots of denim and though novelty textures and weaves are also important, there is a huge demand for vintage-look denims,” she says.

The notion of what constitutes premium or high-quality denim has shifted over time, but what has not changed are the fundamentals, says Baber Sultan, at Artistic Milliners. “It starts with selecting the right fibre. Innovation in weaving has helped improve construction and allowed us to infuse the most rugged, authentic and prized denim with exceptional softness.” But he says that by far the biggest evolution is sustainability. “It pushes us to experiment with greener denim that has the look and feel of what has traditionally been expected of top-quality fabric,” he says.

Advances in technology in spinning and weaving processes, along with the introduction of new fibres, have given denim manufacturers a free rein to design and develop new styles. “It is a garment and fabric that could be described as all-terrain, as it is perfect for almost any type of occasion. Denim is a key part of the fashion world. It lends authenticity in any form,” points out Juan José Lopez, product manager for Tejidos Royo.

Tomorrow’s denims

Artistic Milliners recently launched a new division, Artmill, which it says is the next step in the evolution of its ‘Artistic Milliners Ecosystem’. “This is where we combine what we do best, denim and leading-edge eco-tech, and use them to unlock new frontiers,” says Mr Sultan. The company is introducing denim hybrids, which it calls Art-Cross, combining its most popular constructions and translating them into woven ready-to-dye products. “This offers new possibilities for our clients as you can play with an authentic aesthetic and combine it with characteristics such as flexibility, shape retention and low abrasion resistance. They’re fun and functional all at once,” he says.

Sustainability is another key concern of mills around the world, and Isko has taken many measures to reduce the impact of its activities. “Our main challenge today is to reduce the use of virgin resources,” says Mr Ozden. In the past four to five years, the company has significantly scaled down their presence. Its new collection, presented this April, has 70-80% recycled content, in cotton and in polyester, while delivering the look the market wants, he says. Two new sources of recycled fibre are in development within the textile group. A spinning facility of Isko-owner Sanko Group is testing the new manmade cellulosic fibres made from cotton waste (see article ‘Keeping cotton in the loop’). It has invested in and is testing a technology that separates cellulose from polyester developed by Hong-Kong based textile research centre HKRITA.

Whatever new, or old (think hemp), fibres are introduced, modern mills will seek to preserve the original character and appeal of denim. “It is fairly easy to use recycled cotton yarns, but if a garment doesn’t sell, it is not sustainable,” Mr Ozden points out. The circular solutions Isko is developing need to live up to this incontrovertible standard. “If the second-hand or even third-hand market is to grow, we need to make jeans that last longer,” he says.

This trend can be seen across many mills. “The future of the textile sector is circularity, sustainability and digitalisation,” says Mr Lopez at Tejidos Royo. “We are facing the most important change since the industrial revolution.” He believes it is a true textile revolution. Besides continuous technological innovation, efficiency in industrial manufacturing process and excellence in product, the company is also engaged in the circular economy and new business models. “Our motto is to manufacture better with less. Minimising resources in the production process is key to our business strategy,” he says.

Ultimately, manufacturing a denim fabric capable of lasting through multiple lifecycles could be just another way that it stays true to its heritage. It might even be said that everything must change so that nothing changes.

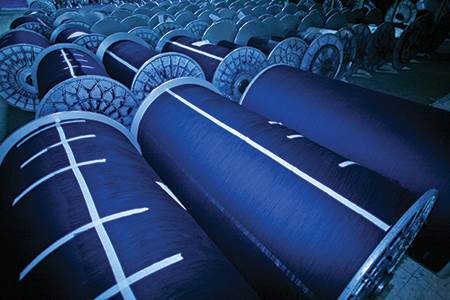

The classic denim fabric is a 3x1 twill in which the outer face will be roughly 70% warp-dominated and blue, and roughly 75% white on the back. Shown here, warp beams at an Isko factory.

Photo: ISKO